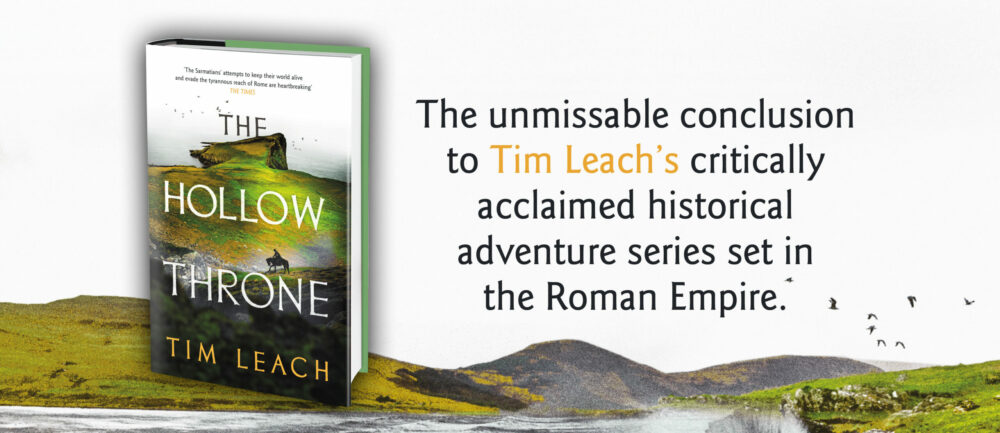

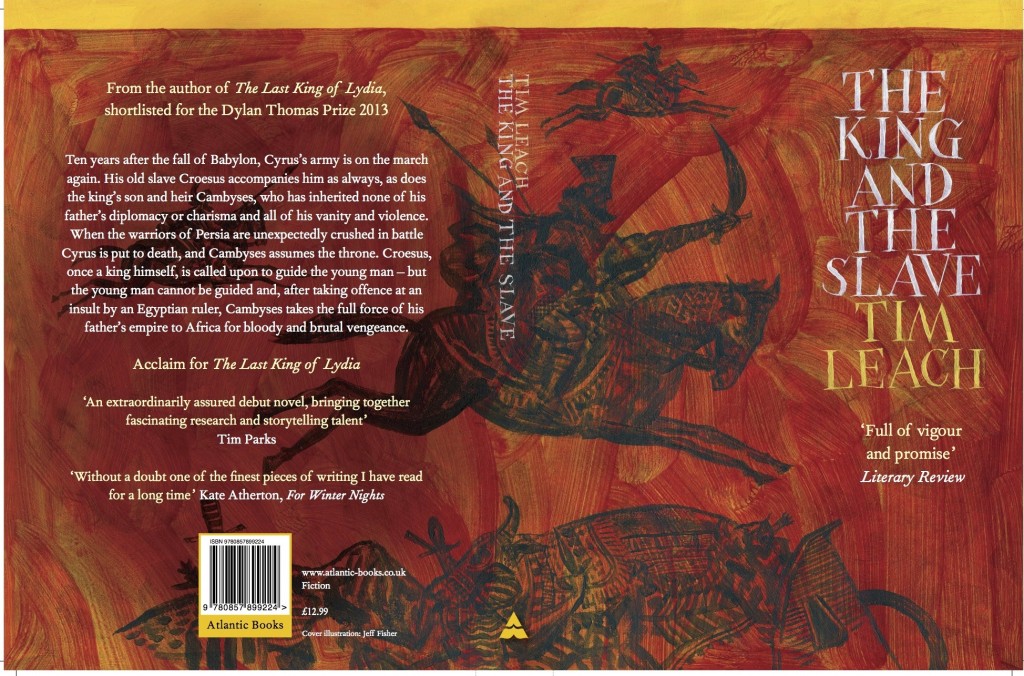

The small paperback of ‘The King and the Slave’ is now out! Portable! Cheap! And found between Halldor Laxness and Steven Leather at all good bookstores…

Author Archives: TimLeach

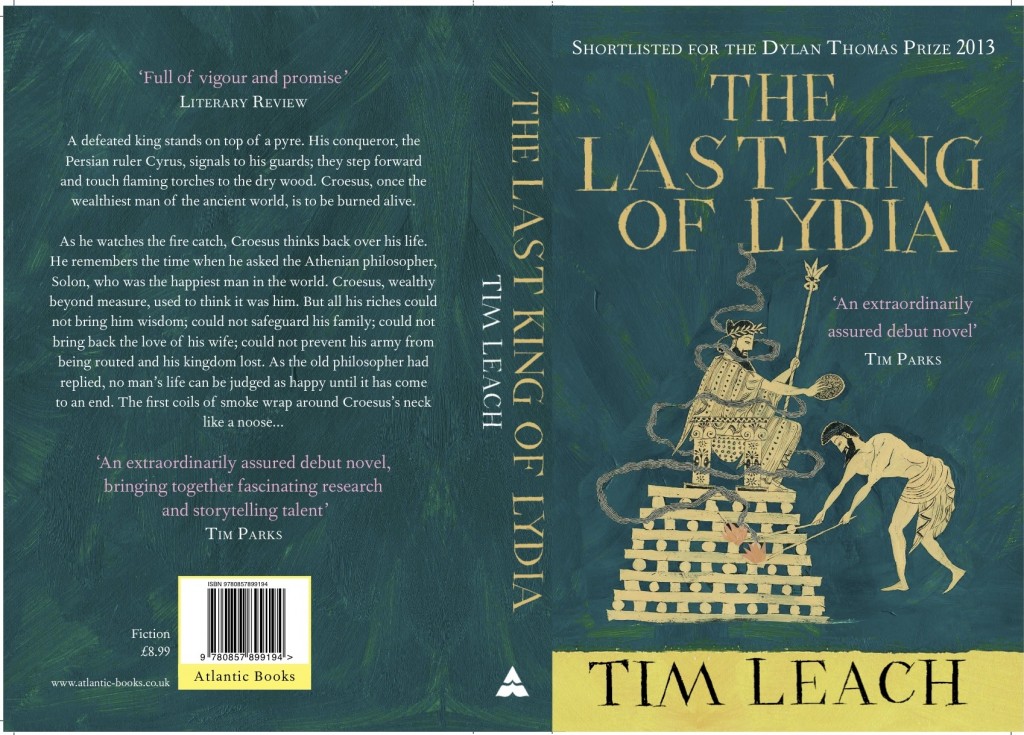

Last King of Lydia Paperback Released!

Cover Art Double Bill

God Bless Us, One and All

In praise of unpublished books

At long last, it’s finished. Against the odds, you’ve planned, drafted and edited your first novel. Now the only question is which publishing path to choose.

Some people will choose to try for the traditional model first, submitting to agents and publishers, with self publishing as a back up option. Others go straight into self pub, believing it to be the newer and better form.

Both paths have their merit, depending on the author and the work. However, I’d like to suggest that you strongly consider a third way.

Don’t publish it.

When you finish your first novel, you should give very serious consideration to pouring yourself a celebratory glass of Scotch, sticking a year’s hard work in a drawer, and starting straight away on the next one.

Why? Because it’s probably not good enough.

It’s a shadowy topic that isn’t always discussed openly, but ply a successful writer with enough wine or whisky, and you might just get them talking about the stinker they’ve got hiding in a desk drawer at home, never to see the light of day. That mediocre novel they turned out when they were first learning the craft. Some have got more than one – two, three, half a dozen. Some have more than ten.

When they finished their book, they didn’t immediately leap into trying to get it published, to get it out to as many readers as possible, to make as much money from it as they could. First, they gave it a long hard look, and they asked – is it good enough? More often than not, for a first time novel, the answer is no. Editing can do wonderful things, but sometimes there are books that cannot be saved, that are too fundamentally flawed. Then they asked, can I do better? And they knew the answer was yes.

I don’t recommend this course of action out of snobbishness, or elitism. It’s because I think it is one of the best things a writer can do to develop their craft. The moment you publish something, you tell yourself that it is of professional standard, that it is worthy of being paid for. Fix that bar too low, and you’ll cease to push yourself as hard as you could. Traditional publishing has a barrier to entry built into it; questions may be asked at how effective or well calibrated it is, but there are plenty of writers who owe their development to the knock backs they got, forcing them to raise their game. Now with the option of self publishing, it falls to writers to exercise restraint and discipline. Not to click publish until they are certain that the work is good enough.

Most self published novels I see aren’t truly terrible. They really aren’t. They’re just very average. Mediocre. Undercooked. The work of writers still finding their voices, writers who are still learning, still a few novels away from producing the real thing. And I believe that you shouldn’t start monetising your art until you have absolute confidence (and trusty external validation) that what you are producing is strong enough. Otherwise, you’re disrespecting both your art form and your readers. You might be stunting your own growth as well.

When I wrote my first novel, I knew it wasn’t good enough. I could have stuck it online, earned a little beer money. The hook was enticing enough, and on a sentence level it wasn’t too bad. But it wasn’t good enough for me, I knew I needed to do better, that I could do better. So it was an important decision for me not to publish it – not to let myself think that it was good enough. Because it wasn’t.

The next book I wrote secured a two book publishing deal. If I’d settled for the quality of the first novel and published it, I might never have pushed myself to make the next one that much better. I owe a lot to that first book I wrote, it taught me so much. But I’m glad I didn’t publish it.

So that first book you’ve finished? Maybe it really is good enough to send to agents, or to publish yourself. You might be an exceptional case, someone who really did crack it first time around. But maybe you should take a moment to congratulate yourself and think on all the things you’ve learned.

Then put that book aside, and start in on the next one. This time, you’ll get it right.

The Imposter and Dylan Thomas

I am not a writer, I am an impostor. That is what I told myself again and again, even after my first novel came out.

Impostor syndrome (the persistent sense that one is an unworthy fraud in constant danger of being found out) isn’t unique to writers. But, working in an insecure profession that requires an exceptional level of self criticism and long periods of working alone, we may be more prone to it than most. So when my book, The Last King of Lydia, was released earlier this year, I greeted the occasion with as much fear as joy. The publishers would soon realise they’d make a mistake, I thought. The critics and readers would let them know that I wasn’t good enough. That I didn’t deserve it.

Even when it was shortlisted for the Dylan Thomas Prize (the winner of which takes home a life changing £30,000), a nagging voice still told me that I was the odd one out, the lucky one on the list. And yet, when we shortlisters gathered in Swansea for a week of readings and events, it turned out this was how all the others felt as well – that they didn’t belong, that they had been the beneficiaries of some unlikely stroke of fortune or lapse in judgement.

Yet I soon saw that none of the others had fluked their way on to the list, that everyone had earned their place. There was James’s relentless force of language and Marli’s mastery of voice, Jemma’s honesty and Majok’s bravery, Prajwal’s effervescent comic warmth and Claire’s imperious command of narrative. And, seeing how they were all so good and yet still so doubting, I began to believe that perhaps I might be like them. That I might not be an impostor after all.

We went out to schools and spoke to students of all ages, gave readings in bookshops and pubs. Again and again we found the common ground amongst ourselves – a love of untold stories, of the musicality of language, of finding ways of answering the seemingly unanswerable questions in our lives through our writing. Together we enjoyed the strange luxury of being taxied around and going out for fancy meals, the celebrity experience of gladhanding luminaries amidst endless photocalls, and, finally, of dressing up and going to a grand awards ceremony, to find out at last who would be chosen.

The tension was agonising as the night drew on, all of us gulping wine like water and trying to sit patiently through the numerous speeches. I didn’t know how I would feel if I won, how I would feel if I lost.

But when at last the announcement came that Claire had won, all I felt was a relief so strong that it was euphoric, a relief that at last I knew one way or the other. Though I’d nursed a secret hope that I might get lucky, I knew deep down that my book didn’t deserve to win – Claire’s wonderful short story collection, Battleborn, really is a cut above it in craft and skill. But though my novel didn’t deserve to win, I thought that it did deserve to be there, that it stood honourably against the best the world’s young writers had to offer. I began the week thinking I was a fraud, and ended it feeling, at last, like a writer.

I hope that the others feel the same. Steinbeck once said that “A writer out of loneliness is trying to communicate like a distant star sending signals…We are lonesome animals. We spend all life trying to be less lonesome. One of our ancient methods is to tell a story begging the listener to say—and to feel – ‘Yes, that’s the way it is, or at least that’s the way I feel it. You’re not as alone as you thought.’” That is the cruel irony of writing – the writer tries to make others feel less lonely, and yet often ends up making him or herself feel more so. And now that it is all over and we’ve all gone our separate ways, this is the feeling I take away: that I am not alone.

Talking is a martial art

Dialogue seems to be one of the areas where developing writers consistently struggle, even if they are strong in other aspects of the craft. I write pretty talky books, and thought I’d share a few principles I try to keep in mind when writing dialogue.

Give dialogue its due

In my novels, I treat dialogue scenes like a kung fu film maker treats his fight scenes – with the greatest craft and care, because I know that they are the main reason my reader has come along for the ride. Not to hear me lecture on my brilliant personal philosophy, or write purple prose descriptions of faraway lands. More than anything, most readers just want to hear convincing characters talking to each other in a believable and interesting way. Too many writers seem to treat dialogue as a chore or an afterthought or a cheap tool for exposition. Never forget, it demands your full attention.

Know what the characters want

This, of course, is a principle that applies to most aspects of narrative fiction, but is particularly glaring in dialogue if it hasn’t been properly thought through. Most bad dialogue is spoken by underdeveloped characters.

A conversation, even a friendly conversation, usually has a competitive aspect. The characters want something, otherwise they wouldn’t be talking, and they are trying to shape the conversation so that it satisfies their want as quickly and throughly as possible. This desire may be concrete (the combination to the vault, the location of the bomb) or it may be more abstract (to assert their world view, to have their actions approved of, to make the other person feel bad about themselves). It’s this tug of war between conflicting desires that gives dialogue energy and tension. Identify their desires and how they conflict, and you’ve got the beginnings of a dialogue structure already.

Your characters can want many things, but I can tell you one thing they don’t want – they don’t want to explain your plot to the reader. The moment characters start mouthing large chunks of exposition for no good reason is the moment your book will be hurled across the room by any vaguely discerning reader.

Know how they’ll try to get it

Once you’ve mapped out what each character wants, you’ve got to think of how they will get it. Sometimes characters will fight fair – they’ll try and use reason and logic and compromise to achieve their goals. Sometimes they will fight dirty – they’ll lie, threaten, bully, flatter, seduce.

Again, think of dialogue like a physical conflict. A fighter is cautious at first, trying to get the measure of his opponent. He’ll try a technique; if it doesn’t work, he’ll try something else instead. If he finds himself winning, he’ll press his advantage aggressively. If he’s losing, he’ll up his defences, try and find an effective counter, and in desperation may do something that’s against the rules, that is morally compromised.

Map out your dialogue scenes like you’re choreographing a fight; plan every punch, lock, throw and counter.

Be Indirect

These techniques of dialogue are many and varied, but almost always, the key to convincing dialogue is having characters approach things indirectly.

In bad dialogue, characters say exactly what they think and feel and want. In real life, we very rarely out and out say these things. We skirt around the truth, hint at it obliquely, misdirect and actively lie. Because the truth makes us vulnerable.

To return to our combative running metaphor, to tell someone exactly what you’re after is the equivalent of a boxer dropping his guard – you may surprise your opponent into making a mistake, but it’s more likely you’re going to eat a right cross to the jaw and be knocked out.

The moment your characters are describing their exact thoughts and feelings is usually the moment when your dialogue is at its least realistic. Besides, if you do this, you’re missing the chance to create some excellent natural tension. It’s the gap between what is felt and said, what is wanted and remains unsaid, that creates tension. In close third person or first person writing, we can directly show the reader this gap between thought and speech, intention and action. So don’t let your characters be fully honest with each other – things will be more interesting that way.

The characters we find most fascinating are the ones who are most mysterious. We don’t know exactly what they want, we can only guess. We don’t know what they’ll do, so they constantly surprise is. Carry this principle through to your dialogue, and you’ll do just fine.

My Friends in the North

Climbers tend to be shipwrecked souls. They have that in common with writers, wanderers who drift from place to place, aesthetes in pursuit of the impossible. The stray writer inevitably seeks London, and, sooner or later a lost climber will wash up in Sheffield, clinging onto the wreckage of the life they used to lead. I was a writer before I was a climber, so it is not surprising that I first went to London and then to Sheffield, and that I came seeking what we always seek in new places, the chance to begin again.

The climbers who come here, they think to stay a while, but not for long. To take some time to heal before they go on to wilder adventures or more ambitious lives elsewhere. And yet, many do find themselves staying. They begin to build a life here, a more permanent one than they first thought they would. They get used to picking newcomers out of the wreckage and offering them a place by the fire.

It is hard to describe why this is. Most passing visitors to Sheffield go away unimpressed. Their eyes wander over the cramped terraces of the suburbs, the ugly sprawl of ringroads and department stores that guards an average town centre, and you know they wonder what the hell you are thinking, living in a place like this. Some pleasant enough parks, a scattering of good cafes and pubs, but it does not convince them.

You take them out into the Peak District, and you see at last a glimmer of appreciation for the endless wooded valleys, the gritstone edges like fortresses on the horizon, the purple of the heather and the golden haze in the sky. And yet it still does not convince. You have to live here to understand.

We’ve come here fleeing one quiet disaster or another, and we survived them. That’s what Sheffield is to me, a place of broken things being forged again. Not a place to be seen, to impress others, but a place to heal. Your friends put you back together in the city, and you prove it to yourself out in the Peak, suspended on a few crystals of grit high above the ground or running with burning lungs up the valleys. Climbing isn’t a game of death, it’s a celebration of living, surviving, moving on. Just as writing isn’t a game of ego and narcissism, it’s finding a way out of a seemingly inescapable trap of the mind, trying showing that way to others.

I don’t know how long I’ll stay here. It could be six months or sixty years, or anything in between. I don’t do much of a trade in certainties or long term plans, it’s not the way of a writer (or of a climber). I could stay or go, and only time will tell.

But there is something special about this place, these people. It’s been a good year, and I hope for another just as good or better. So here’s to another year of golden days on the grit, raucous whisky fuelled nights at the Sheaf View, and rainy days curled up in the Rude Shipyard. And thanks to all those who have made it so easy to call this place home, who plucked me from the wreckage and put me back on my feet again. On this little landlocked island of ours, that few travel to and even fewer leave, we only have each other, and find that, perhaps, it is enough.

Dylan Thomas Prize Shortlist

Absolutely delighted to be shortlisted for the Dylan Thomas Prize (I just found out a couple of days ago.) The final prize is given out on the 7th of November, keep everything crossed for me!

Some thoughts on structuring chapters – answer one question, ask two

I’ve done some creative writing teaching in my time, and when students transition from writing short fiction to novels one of the consistent weaknesses I’ve observed is poor use of chapters. Too often aspiring writers will try and write out a draft without thinking about how they are going to use chapters to control pacing and tension. They seem to have it in mind that they will simply hack it up into roughly even chunks later on, like someone slicing up a loaf of bread. But from the conception of the project, you’ve got to train yourself to process your idea into chapters and sections, it’s part of the novelist’s skill set.

It’s difficult to explain quite how to do this. Much of it, for me, is intuitive. A feel for the flow of narrative is like an ear for music; you know what’s right, but it’s hard to explain why it’s right.

Ask Two, Answer One

The best way that I have found (so far) for expressing the principles of good chapter use is this: a good chapter should answer one question and ask another two. The reader feels that they are getting closer, that they are making progress in understanding the book and the story, but also that the novel is also getting more complex. Satisfaction at progression, but also a hunger to press on and get more answers.

This is a simplification – many chapters will ask and answer many more questions than that. The important principle, at least in the first two thirds of your book, is to make sure that you ask more questions than you are answering. This is part of what generates tension.

Short Term, Long Term

Again, as a broad generalisation, one of these questions will be typically be asked in the beginning/middle of the chapter, and one will be asked right at the end. These questions can be further divided up into short term questions and long term questions.

Short term questions demand immediate resolution, and are usually quite concrete. The hero is tied to a chair – how do they escape? Someone pulls a gun – what is the hero going to do? If you place this question at the end of a chapter, it tends to result in a cliffhanger.

Longer term questions can still be fairly concrete and character related, but will be more overarching (Will those two ever get together? Who is going to win the war?) They may also be abstract or thematic (What can change the nature of a man? Is victory worth it at any price?)

The trick is striking a balance between these – a novel that is filled entirely with short term questions will have an initial insistent pull, but the reader can rapidly get tired of one cliffhanger after another if it doesn’t feel like it is building towards something bigger. Even in the most pacey thriller (where short term tends to dominate), some longer term questions need to be asked. Equally, even a very slow, talky, thoughtful literary novel can do with the occasional cliffhanger on a chapter ending to act as a narrative propellant.

Ending on cliffhanger vs ending on a point of emphasis

The questions you choose to ask and answer are how you control the pacing of your novel. End a chapter on “He raised the gun. He pulled back the hammer. He began to squeeze the trigger.” and you will be increasing the pace of the story. End a chapter on “They sat side by side in silence, and watched as the waves came in.” and you are going to create a pause for thought, have the reader linger on a quiet but significant moment.

To return to that initial idea of music and narrative – a novel is a symphony. You need your crescendos and your diminuendos. Musicality is found through variance, the balance between loud and soft, slow and fast, soft and hard. In narrative, we do this by asking the right questions at the right time.